Franz Marc Biography

Franz Marc was born on February 8,1880, in Munich. According to his first biographyer, Alois Schardt, Marc was so ugly at birth that his father, when taking a first close look at his son at baptism, fainted. Undeterred by the family's reaction, Marc quickly emulated their character, becoming know, while still a baby, as the "little philosopher". His father, Wilhelm, was landscapist of "curiously philosophical character", according to Franz; his mother, Sophie, was an Alsacian from a strict Calvinist tradition. Marc's grandparents, were amateur artists who copied the masters. They and his great grandparents were aristocrats, with friends among artists as well as people of letters.

Following the lead of his family, Marc studied theology intensely. The family contemplated both the spiritual essence of Christianity and its cultural responsibilities. Marc was sufficiently moved by the background and his confirmation in 1894 that, for the next five years, his goal was to become a priest. But he mingled with his theological studies the Romantic literature of both England and Germany. Finally, near the end of 1898, Marc gave up his goal of becoming a priest to study philosophy at University of Munich. But suddenly, in 1900, the ethical, high-minded youth turned to art. He studied drawing first with Gabriel Hackl and then painting with Wilhelm von Diez, both at the Munich Academy.

In the first years of the twentieth century, artistic training in Munich emphasized the traditional verities of academic naturalism and studio production. French Impressionist color innovations were still largely unknown. At this early stage in his development, Marc reflects the thematic concerns of such predecessors as Caspar David Friedrich in that the human being is dwarfed by the awesome appearance of nature.

Marc's stiff studio style begins to undergo a transition in subsequent years due to a variety of French influences. A trip to Paris in 1903 initiated an interest in Impressionism. Unfortunately, Marc's artistic development was accompanied by melancholy and upheavals in his emotional life. His religious outlook was at odds with the Munich youth movement and the city's burgeoning bohemian atmosphere. He spent summers in the mountains in 1905 and 1906 as well as traveling to Greece in 1906, attempting to recuperate from unhappy love affairs. This period of anxiety came to a tumultuous end when, on his wedding night, following marriage to the painter Marie Schnur, he left for Paris. That summer, in 1907, his marriage was dissolved.

Evolving a Style

Marc's sudden trip to Paris in 1907 marks a major turning point in his career. Apparently freed from his period of despondency, he came under the influence of Paul Cezanne, Gauguin, and Van Gogh, all of whom had a profound impact on the young artist. Van Gogh immediately fit Marc's mood:

Van Gogh is for me the most authentic, the greatest, the most poignant painter I know. To paint a bit of the most ordinary nature, putting all one's faith and longings into it - that is the supreme achievement... Now I paint... only the simplest things...

Only in them are the symbolism, the pathos, and the mystery of nature to be found.”

Marc and Van Gogh were clearly kindred spirits. Each saw life in religious yet tortured terms and each found transcendent effects in insignificant themes, echoing Symbolist notions. Like Van Gogh, Marc possessed the idea of the artist as martyr.

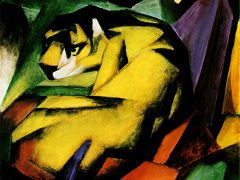

The year 1907 marks the beginning of his sustained preoccupation with a variety of animal subjects. Beside an anatomical interest in these, as in his few pieces of sculpture, Marc's constant thematic concern is the relationship between animal and human spheres. One reason for Marc's interest in animals was that they represented, for him, a spiritual attitude. A critical element in Marc's turn to this subject was a feeling that animals were somehow more natural or pure than people. Moreover, he believed that through animals he could represent his own spiritual feeling.

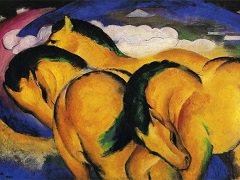

Marc's most important work of 1908 is Large Lenggries Horse Painting. Although he had done several small horse subjects earlier, this work was the largest and most significant to survive. It announces Marc's engagement with the major theme of his career, the horse.

While Marc had painted horses earlier, those versions often portray domesticated or placid animals. But Lenggeries Horse Painting introduces the enormous vitality and vivid rendering that would characterize later paintings. It also shows another aspect typical of Marc's mature work - animals arranged rhythmically, yet with each indicating an individual and potentially emotional or symbolic attitude.

The similarities between the figurative works and the animal subjects, especially with regard to poses evocative of either contemplation, dream, or self-absorption, reinforce the likelihood that Marc transferred to the animal attitudes one associates more easily with humanity.

Maturity

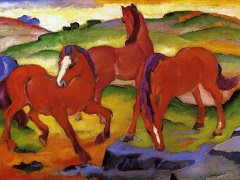

At the start of 1911, Marc painted a large sequel entitled The Red Horses, a work which consolidated and advanced his new maturity. Still rendered with light impasto, like the Lenggries Horse Painting, Red Horses departed from that canvas with the rich formal relationship created between the animals and the landscape, as reflected in the rhythmic curves uniting the torsos and hills. Color is now raised to a brilliant pitch, as the red of the horses contrasts to the blue rocks in the right corner and the yellow ground. In the upper third of the painting, Marc mixed the primaries to produce pinks, violets, and greens, which build toward the mostly white sky.

By early 1911 Marc had already developed a symbolism for his use of color. In this, he followed a pattern established earlier by another early-nineteenth century German Romantic painter Wassily Kandinsky. Marc ascribed spirituality and maleness to blue, femininity and sensuality to yellow, and terrestrial materiality to red. The context in which Marc worked suggests he employed these correspondences programmatically, for Wassily Kandinsky was extremely serious about color symbolism, and the Symbolists, with whom Kandinsky and Marc had much in common, were likewise interested in such ideas.

With Red Horses, Marc was reaching the point of genuine maturity. Coloristic freedom and composition had become integrated with his vision of nature.

Paralleling Marc's artistic evolution was the emotional peace he achieved upon marrying Maria Franck in the summer of 1911, on a trip to England. Maria may have inspired the magnificent Yellow Cow, especially yellow is the color of femininity for Marc. Supporting this possibility is an interpretation of Blue Horse I of the same year, as epitomizing Marc's mood. In each case, Marc's color symbolism reinforces exaggerated archetypal portrayals: the male blue horse is contemplative and spiritual; the yellow female is active and sensual.

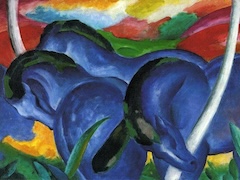

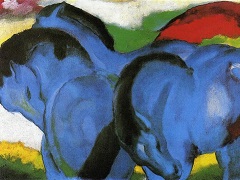

Following Red Horses and Yellow Cow, Marc completed his suite of monumental, primary-color compositions in 1911 with The Large Blue Horses. He returned to the Large Lenggries Horse Paintings for the pose of the animals and for the semi-circular arrangement, with all pointing to the left. The grouping of animals is rather awkward and bulky, as they are bunched in a small, constricted, entirely blue area, with the viewer's vantage point close to the action. Compositionally, the animals are more fully integrated with a hilly landscape than was the case in Red Horses, for the curvilinear rhythm that characterizes the torsos is repeated precisely in the hills.

Der Blaue Reiter and Expressionism

Der Blaue Reiter was founded in Munich in 1911 by Marc and Kandinsky after they resigned from the Neue Künstlervereinigung München due to their differences of opinion with other members of the association. Marc and Kandinsky shared similar ideas on art: both believed that true art should possess a spiritual dimension. Kandinsky's views are outlined in his text Concerning the Spiritual in Art, which first appeared in 1911. For Marc the spiritual aspect of art was perhaps more concerned with representing the inner soul of a being; Kandinsky represented the spiritual by abstract means. Both felt that much of the art of their day lacked any such dimension and thus hoped that Der Blaue Reiter would create a spiritual revolution in art. In addition to Marc and Kandinsky, other members of the group included Macke, Münter, von Jawlensky, the Austrian artist Alfred Kubin, and the Swiss artist Paul Klee. Their work was not united by a particular style but by common objectives in their artistic production. The key events of the group's activities were two exhibitions, in 1911 and 1912, and the publication of an almanac in 1912. Both exhibitions were held in Munich, and subsequently travelled around Germany. They featured works by members of the group and by other artists, including the Spanish artist Pablo Picasso, Delaunay, and the French artist Henri Rousseau whose work was chosen by Marc and Kandinsky because they represented what they believed to be true art. The almanac, which explored the group's shared consideration for the spiritual aspect of art, consisted of a series of essays by its members and was edited by Marc and Kandinsky, who also contributed three essays each. The essays in the almanac are interspersed and accompanied by illustrations which compare art works from different regions and epochs. The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 brought an end to Der Blaue Reiter's activities, but the group's work, together with that of the Dresden-based group Die Brücke, marks the high point of German Expressionism. A brief comparison is drawn between these two Expressionist groups in The Yale Dictionary of Art & Artists:

Where the Brücke artists used distortion to signal tensions in the artist and sharpen viewers' responses, Blaue Reiter artists typically wished to involve us in a more meditative communication. Whereas some of the Brücke artists wished to be seen as 20th-century Germans

developing a truly German art in a country too long dominated by French values and manner, the Blaue Reiter circle was of its nature international, and viewed art in global, even eternal terms.”

The importance of the almanac as evidence of the articulation of Marc's views and ideas cannot be underestimated. In his essay in the almanac entitled 'Spiritual treasures', Marc discusses the idea of the "mystical inner construction," referring to the sense of spirit which gives a being or place its unique character. Marc explores this theme through the figures present in works by El Greco and the landscapes by the Paul Cézanne. The use of the word "mystical" encourages both the impression of something which is not immediately obvious or material and a sense of intrigue. Marc seemed to be striving to achieve and to capture this "mystical inner construction" in his paintings of animals. Another essay entitled 'The "savages" of Germany' can further aid an understanding and appreciation of Marc's paintings and the objectives of his artistic production. In this essay Marc identifies "symbols that belong on the altars of a future spiritual religion" within the work of Kandinsky and von Jawlensky. He implies that this is a basis for the work of Der Blaue Reiter and consequently for his own work. Hence, it appears that Marc was preoccupied with representing the inner being of his subject, and that spirituality and religion were at the forefront of his objectives.

Abstraction

By late in 1913 Marc was increasingly organizing his vision with an abstract vocabulary. A language largely evolved from Wassily Kandinsky, and Futurism, as well as Macke's color compositions of 1912, this abstract mode unified his subject matter while reducing the melodrama. Abstraction, in Marc's view, became a means of expressing the eixstence of one creative law of the universe. Hence, his subject matter while reducing the melodrama. the horse is no longer shown in individual terms of heroism or pathos but rather as an aspect within a universal field of forces. That field, whether determined by a generative or destructive law or by an overall "structure of universe," occupied Marc in his final paintings.

Stables, 1913, the last major work based on the horse theme, aptly demonstrates Marc's late approach to his favorite subject. He no longer show the world in representational terms or as seen from an individual animal's advantage point. Rather, an overall pictorial structure of large diagonal crosses holds within it a group of red, blue, and white horses. Opposed to earlier gatherings, the animals in Stables have a more rigid and schematic portrayal. the circular and semi-circular body parts form a rhythm across the surface which is contrasted with the angular lines of the stable structure.

Frequently in 1914 Marc presents vibrant formal relationships that epitomize the most extreme moments in nature. for example, in Fighting forms, 1914, he dramatically depicts red and blue areas in conflict; in Animal in Landscape, 1914, he created a similar aura of intense energy, with raging linear, coloristic, and planar juxtapositions, characteristic of Marc's finest work of 1914. Both creation and apocalypse assume similar appearance for Marc, as the visual attributes of Painting with Bulls, which is without clear suggestions of conflagration, appear, also, in Fate of the Animals. Thus, Marc's aim in 1914 is to show a singular red-versus-blue relationship underlying all events, like a law of nature. This contrast was the dominant one in Blue Horses of the three ears earlier.

We have seen that Marc's career in part consisted of metamorphosing themes he had already considered, as in the case of his treatment of human figures and animals, and the absorption of human qualities into the animals.

Marc's conclusion that animals, like humans, were ugly became an important motivation for his concentration on nostrils. In emphasizing snouts, he chose one of the least attractive attributes of animal, as if to turn himself from his fascination with their dynamic, physical character to an aspect of no inherent beauty or interest.

Broken Forms is an example of Marc's final series of works, a group from 1914 with tile such as Playing Forms, Abstract Forms, Fighting Form, Higher Forms, and Small Composition I, II, III, and IV. In these, Marc has taken the step to virtual abstraction, a move he had continuously approached. Apparently, as with the earliest horse paintings, Marc was somewhat dissatisfied with these works, however, and, calling them experiments, he preferred not to exhibit them.

In the spring of 1914 Franz and Maria Marc bought a small country house in Ried. According to Kandinsky, this purchase was one of "Marc's greatest wishes come true." He was even able to keep a dog and a tame deer there. But in August of 1914, at the outbreak of the war, Marc volunteered. Kandinsky visited him to say "Auf Wiedersehen." but Marc replied "Adieu." Within two months, Marc's first personal indication of the war's magnitude occurred; Marc died in battle in September at the age of twenty-seven.

Marc wrote and drew extensively at the front. His drawings show a remarkable looseness and facility, for the most part combining figurative elements within a Cubist of Futurist framework of lines. Frequently still, innocent animals are depicted, yet now within a gradually tightening web of force lines that are reminiscent of Marc's vision of destruction, Fate of the Animals, 1913.

while cataclysmic events occurred around him, Marc nevertheless theorized on the supposed benefits of war, including the thought of a spiritual breakthrough and redemption through suffering. He was so moral in his belief in the eventual beneficent effects of the war that he could ignore the fact that patriotic allegiances fueled the war and caused his presence. Finally, he interpreted events in a more fatalistic way. Like the animals who had become simply motifs in a large scheme, he saw himself at war in similar terms. In the war Marc was forced to rationalize his aim, but the conflicts and questions that resulted disturbed him profoundly. Paul Klee was "afraid that he might be a completely different man some day," as if his delicate balance might not withstand reality. The trauma of the war for Marc was such that, at the end, only death could give him relief. In that state his own innocence could be restored. One of Marc's last letter, before his death at Verdun in 1916, concluded on this notes:

I understand well that you speak as easily of death as of something which doesn't frighten you. I feel precisely the same. In this war, you can try it out on yourself - an opportunity life seldom offers one...nothing is more calming than the prospect of the peace of death...the one thing common to all. It leads us back into normal "being". The space between birth and death is an exception, in which there is much to fear and suffer. The only true, constant, philosophical comfort is the awareness that this exceptional condition will pass and that "I-conciousness" which is always restless, always piquant, in all seriousness inaccessible, will again sink back into its wonderful peace before birth... whoever strives fro purity and knowledge, to him death always comes as a savior.”

Conclusion

Franz Marc contributed to the vision of abstraction in its second wave, 1911-14, by wedding an Expressionistic outlook to the new pictorial developments emanating from France. There, formal innovations were largely an end in themselves. But in the hands of Franz Marc and Wassily Kandinsky, arbitrary color, faceted planes, and pictorial structure became modes with which certain deeply held themes could be stated. Marc's achievement was in effect creating works of art that, through abstract means, evinced his conception of the overall unity and character of nature.

As a founder of the Blue Rider, Marc holds a place in the theoretical impact of this pivotal movement of future developments, such as Dada, and Bauhaus. More specifically, Marc was to have an influence on his colleague Paul Klee. the latter described their relationship as a pair of overlapping circles, with a "relatively large common area." Although a year younger, Marc reached artistic maturity ahead of Klee. In general, the overall delicacy of touch and transparency in Marc's watercolors are close to the work of Klee after 1914. Also, certain motifs appear fist in Marc's work and subsequently in Klee's; for example, Marc's use of triangles and upward-moving forms to imply aspiration became a constant in Klee's art. The two shared much in common theoretically, especially the desire to see through a transcendent vantage point. reinforcing their common belief in fate was the fact that, on the day Klee received word from Maria Marc of his friend's death, he was drafted.

The desire by the German wave of abstractionists to unite the new pictorial means from France with ambitious or transcendent subject matter, or both, quickly became the goal of subsequent movements of twentieth-century abstraction. While Marc was not alone in possessing lofty aspirations, he and Wassily Kandinsky established a critically important step in making Cubist and Fauvist harmonies apply to an elevated concept of subject matter. For instance, the desire for the content of epic proportions became a touchstone in the work of Kasimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian, and then, among American Abstract-Expressionists Jackson Pollock, and Jasper Johns.